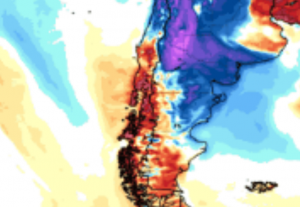

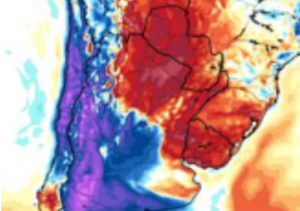

Over the weekend, Europe witnessed temperature extremes rarely seen so early in the year. On June 28, El Granado in southern Spain registered a blistering 46.0 °C, eclipsing its own national June record and marking the highest reading on the continent so far this summer. In France, Météo-France confirmed a new all-time national high of 46 °C at Vérargues and 45.9 °C at Gallargues-le-Montueux—both measurements exceeded the previous French record of 44.1 °C set in 2003. Bosnia and Herzegovina also saw unprecedented highs: Doboj climbed to 38.2 °C and Sarajevo to 38.8 °C, each shattering local June records. Meanwhile, the United Kingdom struggled under its own early-season heat, with southern England topping out at 34 °C on Monday and forecasts warning of 35 °C on Tuesday—potentially the hottest Wimbledon opening in history. Across a mere 48 hours, countries from Iberia to the Balkans to Britain have recorded temperatures 10–15 °C above their long-term June averages, underscoring the extraordinary nature of this event.

The epicentre of the heat dome remains the Iberian Peninsula, where sweltering highs of 42–46 °C have pushed emergency services to the brink. Portugal’s Beja, Évora and Lisbon endured readings around 43 °C under prolonged red-warning alerts, prompting authorities to restrict outdoor work and open public swimming pools to ease the strain on residents. In Italy, regions including Tuscany, Lazio and Calabria enforced bans on midday field labor as dozens of cities—Rome and Milan among them—were placed on maximum heat alert. France’s southern departments, from Bouches-du-Rhône to Pyrénées-Orientales, braced for temperatures 10–15 °C above seasonal norms, with forecasts warning of sustained highs into midweek. Eastern Europe also felt the pressure: Serbia and Bosnia reported record after record, while the Balkans at large experienced temperatures more typical of August than late June.

Infrastructure and public services are already creaking under the heat’s weight. In Bosnia, the temperature-induced distortion of rails forced a shutdown of the Banja Luka–Čelinac line, highlighting the subtle yet serious impacts on transport networks. The London Fire Brigade, anticipating wildfires akin to recent Mediterranean blazes, issued urgent warnings as grass and scrub fires surged around the capital. In Greece, authorities closed coastal roads near wildfire hotspots and evacuated visitors from the Temple of Poseidon amid spreading flames. Marseille offered free pool access to cope with soaring urban temperatures, while Sicily and southern Italy curtailed outdoor work hours to protect laborers from dangerous heat stress. Health services across Europe remain on high alert, issuing guidance for hydration, shade breaks and monitoring of vulnerable groups.

Perhaps most striking is the timing. This onslaught of heat has struck just one week after the Northern Hemisphere officially entered summer on June 21. Climatologists note that “June is fast becoming the new July,” with extreme heatwaves arriving earlier and lasting longer due to global warming. The convergence of a robust anticyclonic dome over western Europe and warm, dry air from North Africa set the stage for record temperatures well before the traditional peak of summer. Night-time lows have also remained unusually high—often above 20 °C—offering little respite and compounding the public health challenge. Summer preparedness plans, built around July–August peaks, are being tested far sooner than expected.

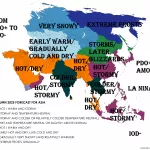

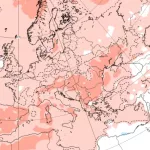

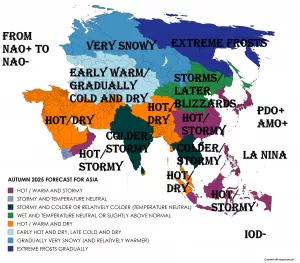

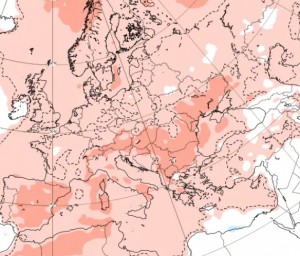

Looking ahead, long-range forecasts from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts and Copernicus point to a continuation—and possible intensification—of this trend. Elevated North Atlantic sea surface temperatures, which correlate strongly with European summer heat, are signaling a season likely to be one of the hottest on record. The World Meteorological Organization warns that one of the years 2025–2029 could surpass 2024 as Europe’s warmest ever, driven by repeatedly early and intense heatwaves. Seasonal outlooks now predict the worst-hit regions will remain the Iberian Peninsula, southern France, Italy and the Balkans, with the UK and parts of Central Europe also at risk of sustained extremes.

This summer’s opening act has already drawn an unbroken line between the areas sweltering today and those flagged as most vulnerable in seasonal models. Regions under heat dome influence now correspond exactly to the zones forecast for the greatest temperature anomalies. Conversely, northern latitudes—from Scandinavia to northern British Isles—may see more moderate conditions, though isolated heat spikes cannot be ruled out. As Europe confronts this premature furnace, the alignment between forecasted and observed hotspots underscores the urgent need to bolster heatwave resilience—from infrastructure hardening to early warning systems—well ahead of the season’s traditional peak.