I. Introduction

The French Revolution is remembered for stormed prisons, guillotines, and a clash of classes. But one of its least visible but most powerful causes was the weather. Extreme climatic events, poor harvests, and the resulting spike in grain prices created the economic pressure cooker that would explode into revolution. This article investigates how weather anomalies—especially in the 1780s—played a central role in pushing France toward one of the most profound political transformations in history.

Illustration picture: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liberty_Leading_the_People

II. France on the Eve of Revolution

In the 1780s, France was:

- An agrarian society (about 80% rural population)

- Deeply indebted due to wars (especially the American War of Independence)

- Dependent on subsistence agriculture

- Governed by a monarchy under increasing pressure for reform

Despite philosophical ferment among elites, it was the economic distress of the common people that turned rumbling discontent into open rebellion.

Agrarian France in the Middle Ages. Source: http://www.1704.deerfield.history.museum/scenes/nsscenes/lifeways.do?title=French

III. The Central Role of Grain in 18th Century France

Bread was not a luxury—it was a staple of life. For most of the lower classes, bread provided:

- 70–80% of daily caloric intake

- The main source of food security

When grain prices rose, people could not eat.

“Grain was not just an agricultural product. It was the currency of survival.”

Source: https://moonapeuro.weebly.com/causes-of-the-french-revolution.html

Here is how grain formed the basis of livelihood:

| Item | Importance |

|---|---|

| Wheat/Rye | Main grains used for bread |

| Bread | 70–80% of caloric intake |

| Grain Price Spikes | Triggered riots and revolt |

| Income to Bread Ratio | >50% of income spent on bread in 1789 |

IV. Climate, Agriculture, and the Pre-Revolution Economy

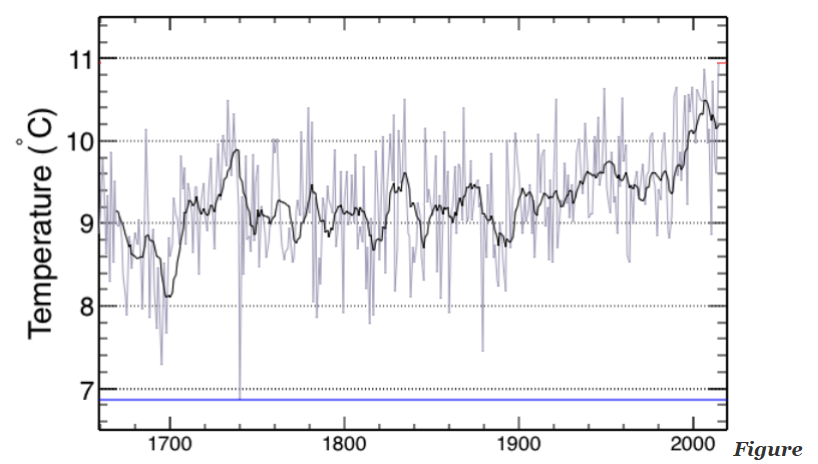

The Little Ice Age (1300–1850) brought:

- Colder winters

- Shorter growing seasons

- Frequent harvest failures

These changes weakened the agricultural system. With no modern fertilizers, no food imports, and low reserves, even a single bad harvest could create massive hunger.

Climate vulnerability meant that the economy of daily bread was also an economy of weather dependency.

Central England Temperatures. Source: https://euanmearns.com/the-end-of-the-little-ice-age/

Source of 3 pictures above: file:///C:/Users/marek/Downloads/bams-1520-0477_1990_071_0033_ghetws_2_0_co_2.pdf

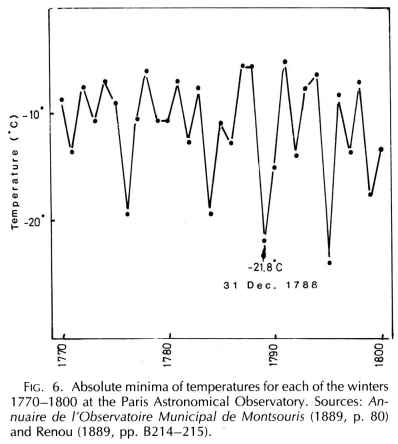

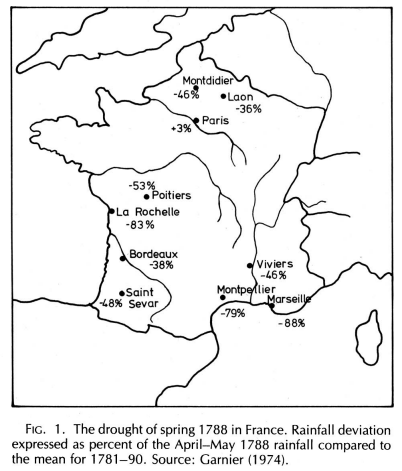

V. The Great Famine of 1788–1789

The winter of 1788–1789 was one of the coldest in French history:

- The Seine River froze

- Transport was halted

- Livestock died from frost

- Spring floods ruined fields

These led to crop failure and skyrocketing bread prices. Hunger intensified:

| Effect | Consequence |

|---|---|

| Frozen rivers | Trade interruption |

| Autumn sowing destroyed | Wheat shortage |

| Meltwater floods in spring | Further crop damage |

| Resulting harvest | One of the worst in French history |

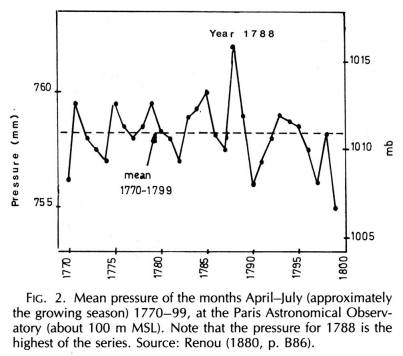

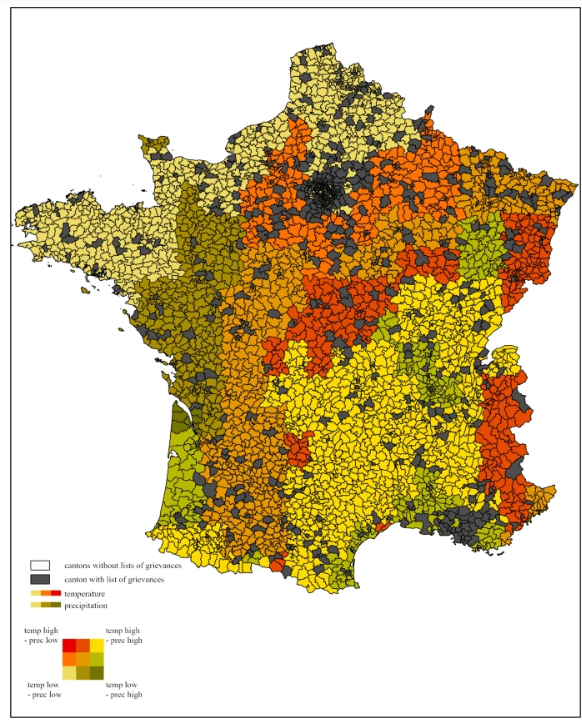

Geographic Distribution of Temperature and Precipitation in the Growing Season of 1788 in France. Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10887-023-09230-y

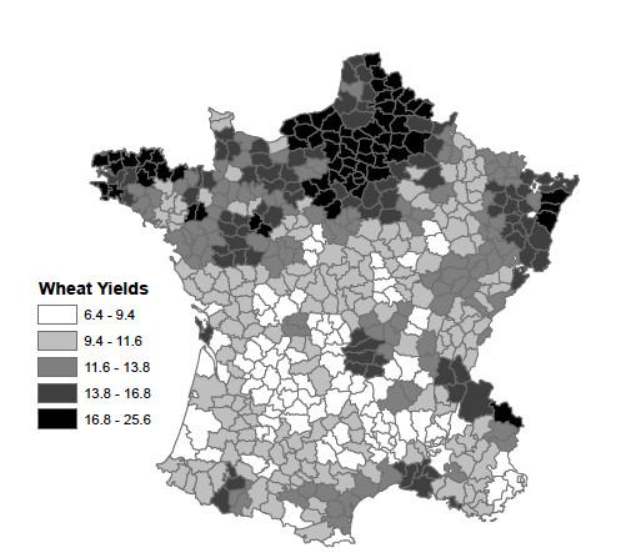

Wheat Fields. Source: https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/economic-consequences-revolutions-evidence-1789-french-revolution

VI. Volcanic Eruption and a Global Cooling Effect

In June 1783, the Laki volcano in Iceland erupted, spewing 120 million tons of sulfur dioxide.

Climatic Effects of Laki:

- Summer 1783: “Dry fog” and hazy skies across Europe

- Winter 1783–84: Extreme cold, one of the coldest in 500 years

- 1784–1788: Crop failures and erratic weather

This volcanic winter reduced sunlight, dropped temperatures, and devastated crops.

| Year | Weather/Impact |

|---|---|

| 1783 | Dry fog, crop stress |

| 1784 | Freezing winter, famine |

| 1785–87 | Unstable summers, poor harvests |

| 1788 | Worst harvest in a generation |

French Countryside after Laki Volcano Erruption in Iceland after 1783. Source: https://miro.medium.com/v2/resize:fit:1280/1*Pm1eRczaTYJv17JlCBQdKQ.png

VII. Grain Prices and Popular Discontent

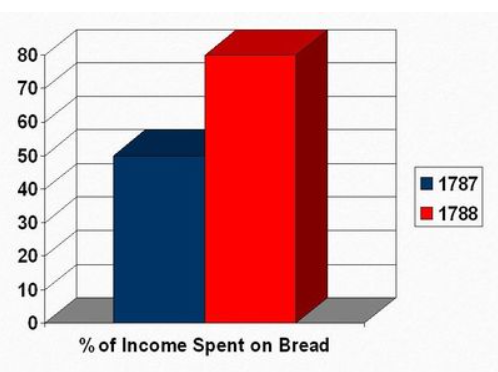

As grain supply shrank, prices soared. A Parisian worker had to spend:

- ~50% of wages on bread in 1787

- ~80% by mid-1789

Here’s a simplified view of wheat prices in Paris:

| Year | Price per setier of wheat (livres) |

|---|---|

| 1786 | 28 |

| 1787 | 35 |

| 1788 | 38 |

| Mid-1789 | 50–55+ |

Result: Unrest grew, especially in cities where dependence on purchased grain was highest.

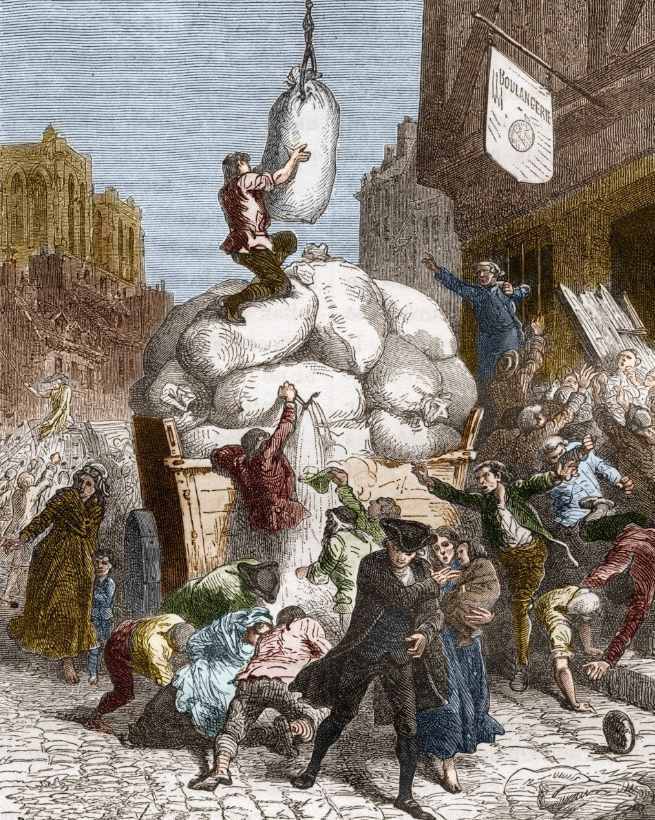

Flour Wars in France in 18th century. Century. Source: https://maxpuckett.umwsites.net/2023/07/20/french-bread-and-why-it-caused-riots-pt-3-14159-on-bread/

VIII. Bread Riots and Urban Unrest

Bread riots became common:

- April 1789: The Réveillon riots in Paris over bread prices

- July 14, 1789: The storming of the Bastille

- October 5–6, 1789: Women’s March on Versailles, chanting “Du pain!” (Bread!)

The crowd believed that the monarchy had failed in its most basic duty: to feed the people.

Fall of the Bastille. Source: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/fall-of-the-bastille/

IX. The Moral Economy of the People

The concept of the moral economy meant people believed that:

- Food should be affordable

- Merchants who hoarded grain were evil

- Justice could be enacted by popular action

Thus, many riots were not criminal in nature, but moral uprisings.

“If bread is life, then injustice in bread is injustice in life itself.“

The Execution of Marie Antoinette. Source: https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2012/07/13/156722719/let-them-eat-kale-vegetarians-and-the-french-revolution

X. The Role of Rural Peasantry

While urban hunger drove revolution, the rural peasants also suffered:

- Feudal taxes on top of grain shortages

- Rumors that nobles were hoarding food or burning crops

- The “Great Fear” of July–August 1789 led to mass peasant revolts

Peasants destroyed seigneurial records, attacked manor houses, and forced change.

| Peasant Actions | Effects |

|---|---|

| Refusing feudal duties | Undermined aristocratic control |

| Attacking food transports | Created chaos in grain distribution |

| Demanding tax relief | Contributed to revolutionary demands |

XI. The King, the Economists, and the Weather

Louis XVI relied on advisors like Jacques Necker, who promoted:

- Free grain trade

- Minimal price controls

But this liberal economic model worsened the situation. Free-market prices meant that:

- Grain flowed to cities where prices were higher

- Rural areas were abandoned to famine

- Speculators profited while people starved

The monarchy’s failure to regulate grain markets fueled rage and revolutionary sentiment.

Percent of Income Paid in Taxes. Source: https://moonapeuro.weebly.com/causes-of-the-french-revolution.html

XII. Weather, Symbolism, and Revolutionary Imagination

The weather wasn’t just materially destructive—it was symbolically powerful:

- Storms = anger of nature

- Comets = signs from God

- Floods = purification and renewal

Revolutionaries saw the sky as a judge. Nature itself was on the side of the people.

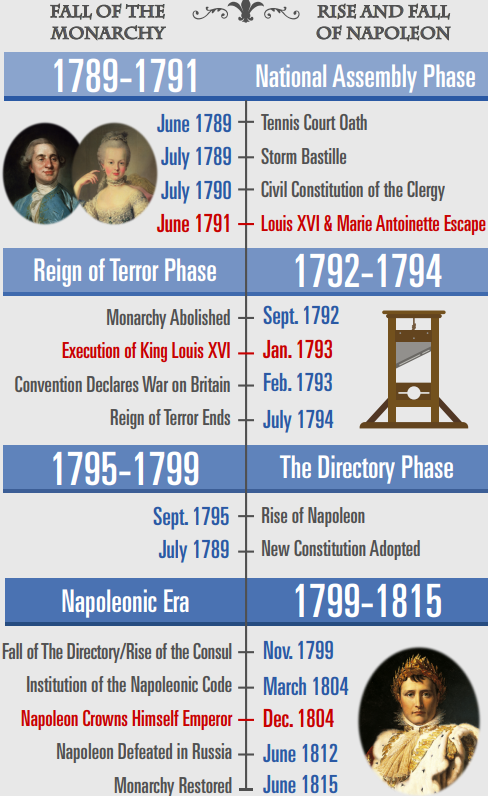

XIII. Climate History and Historical Memory

Recent research by historians like Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie and John D. Post shows:

- Major climate anomalies coincide with social collapse

- Climate history is essential to understanding human history

- The French Revolution fits this pattern: weather stress → food crisis → revolt

French Revolution Timeline. Source: https://assets.ltkcontent.com/files/French-Revolution-timeline.pdf

XIV. Lessons for the Modern World

Today’s world is more globalized, but still vulnerable:

- The 2007–08 food price crisis triggered unrest in 30+ countries

- Climate change threatens food security globally

- Weather shocks can still fuel revolution, especially where governments fail to protect the poor

| Then (1789) | Now (21st century) |

|---|---|

| Crop failure → famine → revolt | Drought/conflict → migration/unrest |

| Bread riots | Food riots (e.g. Tunisia, 2011) |

| Weather + injustice = uprising | Climate + inequality = instability |

XV. Conclusion

The French Revolution was not caused by ideas alone. It was fueled by hunger, driven by cold, and ignited by injustice. The weather and the price of grain were not just background details—they were triggers.

When a nation starves, it speaks through revolution. And in 1789, France spoke with thunder and fire, ushering in a new age—where even kings could fall to cold winds and empty stomachs.

After the French Revolution came the Napoleonic Wars and the Revolution in 1848. Soruces: https://notevenpast.org/napoleon-russia-1812, /https://www.livescience.com/how-many-french-revolutions.html