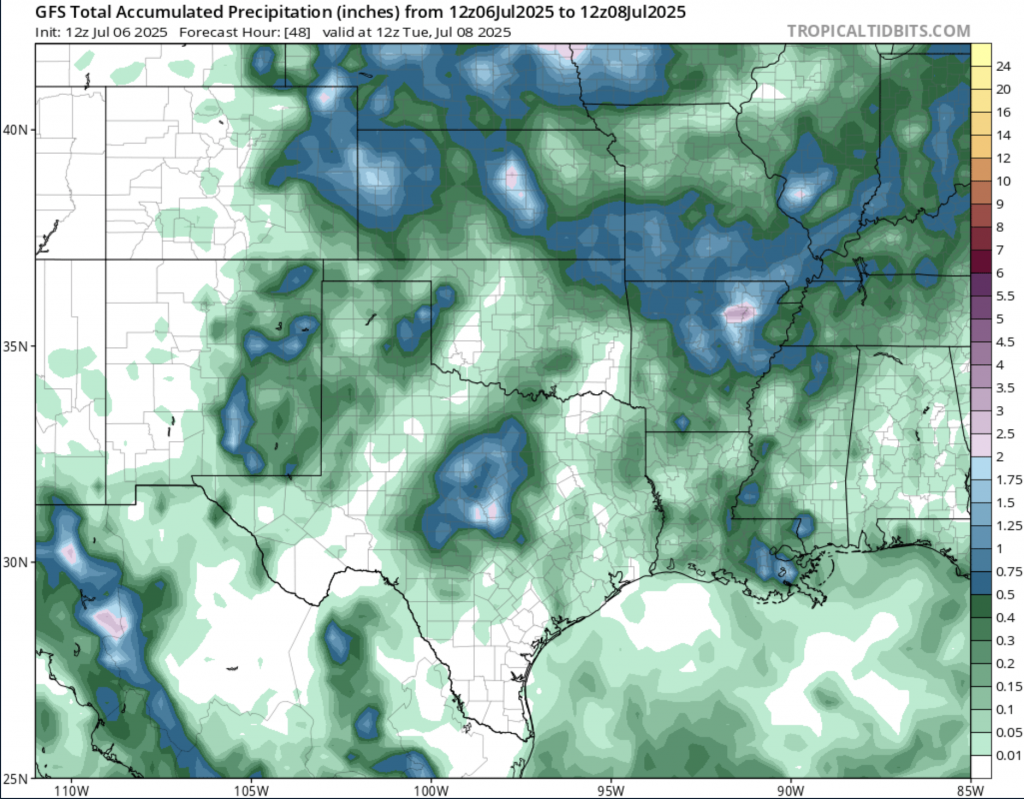

Just before dawn on July 4th and into July 5th, 2025, Central Texas’s Hill Country was engulfed by a deluge of historic proportions. Radar and official measurements confirmed extraordinarily intense rainfall — 300–380 mm (12–15 inches) in just a few hours, far exceeding typical predictions. One gauge near Streeter recorded over 518 mm (20.33 in) of cumulative rain, with peak hourly rates surpassing 127 mm/hr (5 in/hr). This concentrated storm over the same drainages supercharged the Guadalupe River watershed through the steep terrain—turning salvation into calamity in mere minutes. Texas’s Hill Country, which includes areas like Kerrville, Fredericksburg, and parts of the Edwards Plateau, typically receives 70 to 100 millimeters (2.75 to 4 inches) during the month of July. This means over three to four times the total amount of rain expected for the entire month of July fell in just a few short hours.

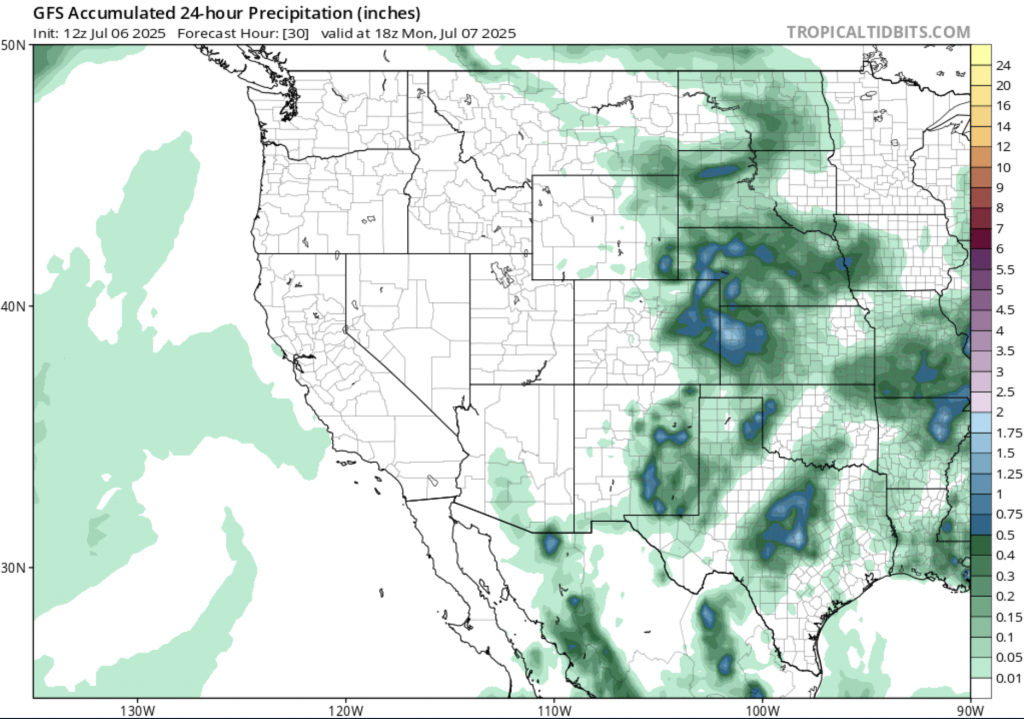

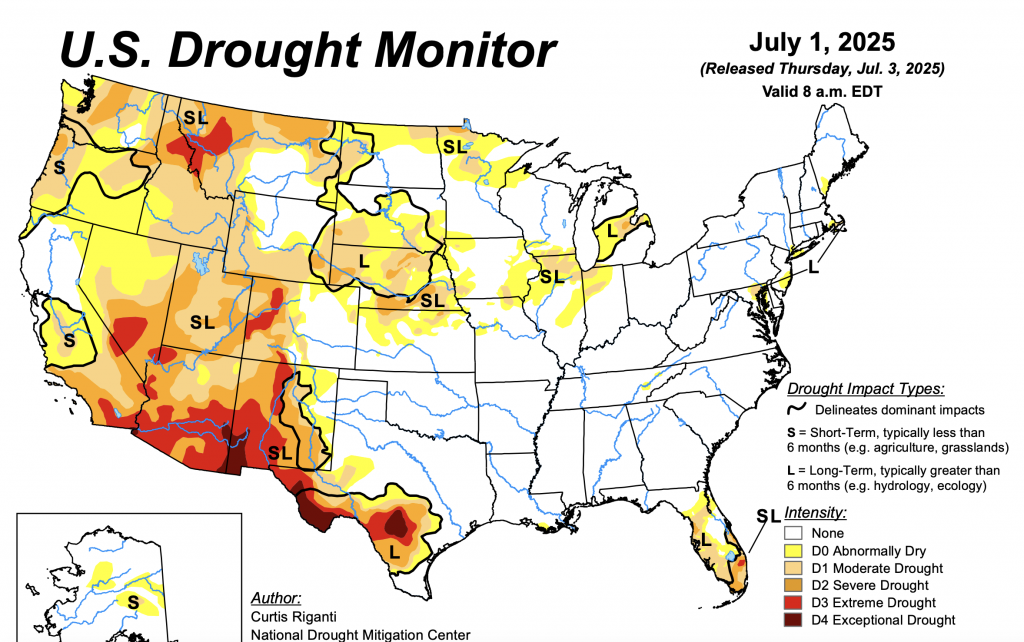

Before the event, the region was experiencing a prolonged multi‑year drought that hardened soils and reduced natural absorption—creating perfect conditions for rapid runoff. The parched earth acted like concrete; when torrential rains finally arrived, water surged straight into creeks and rivers instead of soaking in. Combined with Central Texas’s characteristic limestone hills atop Flash Flood Alley, this hydrological setup amplified the flood risk, accelerating river surges within hours. The area is called Flash Flood Alley due to the steep, rocky limestone terrain, thin soil, and convergence of Gulf moisture with inland air masses — all of which combine to funnel water into vulnerable creeks and rivers.

Geographically, the disaster centered on the Guadalupe River and its forks. In Hunt, the river leapt from roughly 1 m (3 ft) to an astonishing 9 m (29 ft) in just two hours, then surged an additional 6 m (20 ft) in Comfort and Kerrville. Tributaries feeding the system funneled every drop from slopes into a violent torrent, obliterating infrastructure—bridges and roads vanished in minutes. More flash-flood emergencies followed along Lake Travis and the San Gabriel River, highlighting the broader regional danger.

Forecasts initially suggested 75–175 mm (3–7 in) of rain, yet the actual amounts were double those in many locations. While the National Weather Service did issue watches and warnings—with even a flash‑flood emergency overnight—some locals reported the volume of rain as far beyond expectations. Critics allege that past staffing cuts to the NWS impaired local forecasting resolution, though meteorologist unions counter that offices had adequate coverage. The resulting discord has intensified debate over resourcing and forecasting precision.

The human cost has been staggering: as of July 6th, at least 82 people have died, including 28 children, with another 28 still missing. Entire camps, especially around Camp Mystic, were overwhelmed—the Guadalupe River overtook cabins and roads in minutes. Over 850 people were rescued, many by helicopter, but more than 200 remain displaced, their homes destroyed amid debris and erosion. Infrastructure damage includes washed-out roads, collapsed bridges and widespread communications outages; rail and air travel disruptions were reported as regional airports flooded and tracks buckled.

Financially, recovery costs are expected to be steep. Damages to homes, roads, utilities and businesses, combined with extraordinary emergency rescue and healthcare efforts, point to hundreds of millions of dollars in claims and public spending. The insurance industry has signaled this could be one of the costliest flash‑flood disasters in Texas history, surpassing major events like Hurricane Harvey. The federal disaster declaration from the White House signals forthcoming FEMA assistance, though total recovery funding is still pending.

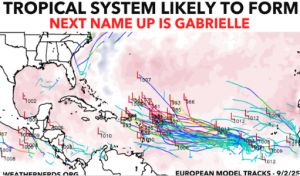

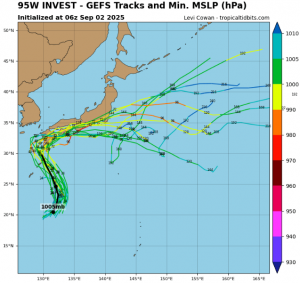

Looking ahead, forecasters caution that although short-term showers may taper, additional bands of tropical moisture linger — particularly the remnants of Tropical Storm Barry — keeping flood risk elevated. With summer thunderstorms common and climate change increasing atmospheric moisture by 20 percent since the 1950s, Texas is entering a season that amplifies flash flood potential. Experts stress that history—the floods of 1987, 2002, 2018—has shown Central Texas is repeatedly vulnerable, often with little to no warning to residents. Given the region’s landscape and cyclical vulnerability, experts warn that without improved warning systems, updated land-use planning, and modern flood monitoring, communities will remain at risk of rapid-onset, deadly flooding in the years to come.